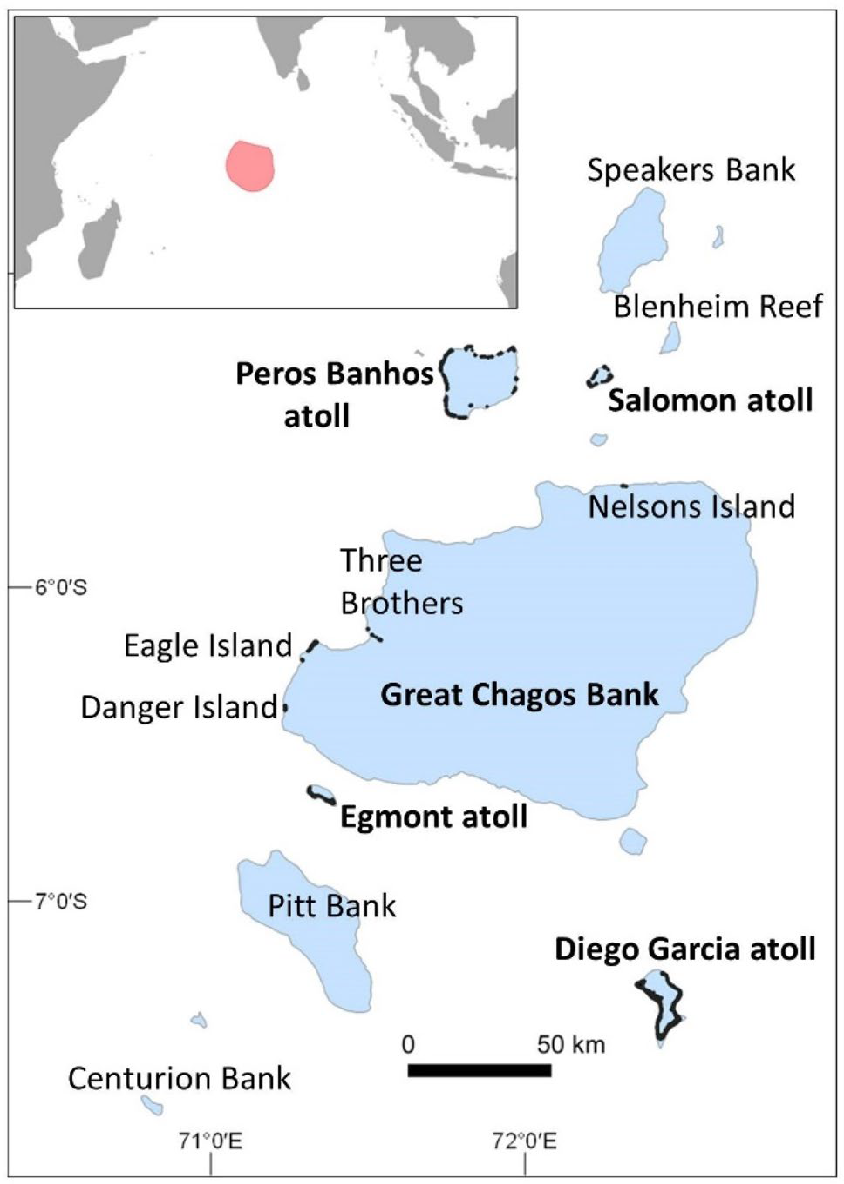

The archipelago is made up of 58 islands with a land area of only 56 km2 of which only the most southerly atoll, Diego Garcia, is inhabited as a military base. The archipelago comprises more than 60,000 km2 of shallow limestone platform and reefs, including the Great Chagos Bank, described as the world’s largest atoll structure, covering an area of over 12,000 km2.

In 2010, the BIOT Marine Protected Area (MPA) was designated, covering an area of almost 640,000 km2, with no fishing or other extractive activities permitted. The BIOT MPA incorporates the marine elements of 5 strict nature reserves. Additional marine protection is found at the restricted area and Ramsar site on Diego Garcia (covering a total area of 350 km2).

The tropical Indian Ocean has experienced rapid basin-wide sea surface temperature (SST) warming, with an average rise of 1.0°C (0.15 °C/decade) during 1951–2015, faster than the global average.

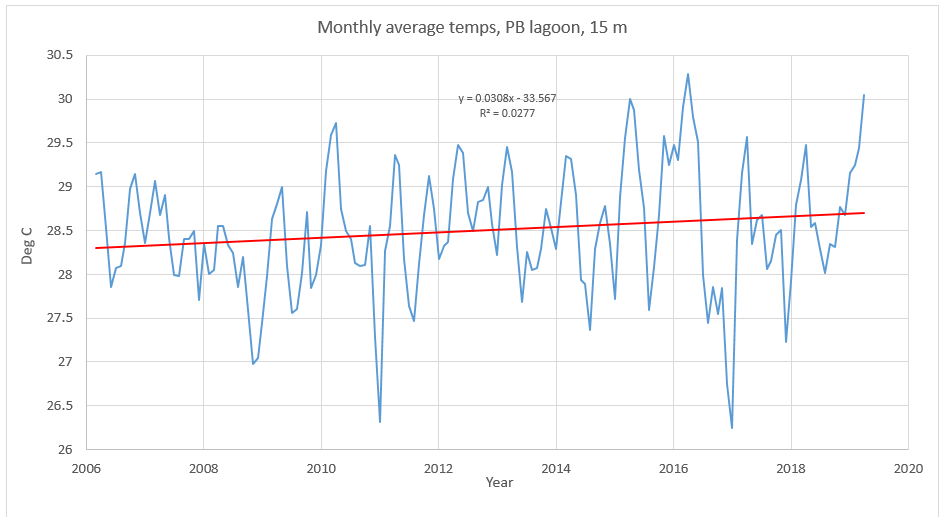

Since 2006, direct sea temperature measurements have been taken in BIOT across atolls at depths of 5m, 15m, and 25m, all of which show an overall rising trend of between 0.3–0.4˚C per decade (Fig 2).

Mass mortality of corals is often triggered when sea temperatures over 29.5˚C persist for 10 or more ‘degree heating’ weeks, as recorded across the archipelago in 1998 and in 2010, 2015, 2016, 2019 and 2020. Models project more frequent and severe marine heatwaves over the coming decades, with annual severe bleaching predicted by 2036 across the Chagos Archipelago under a business-as-usual emissions scenario.

Figure 2. Temperature in Peros Banhos lagoon at 15m depth (Sheppard et al., 2019).

Conditions in the region are strongly affected by the extreme positive Indian Ocean Dipole (IOD), an irregular east-west oscillation of SST across the Indian Ocean that in its positive phase can have effects that extend into BIOT waters. This could increase storm activity in the region and lead to more coral damage.

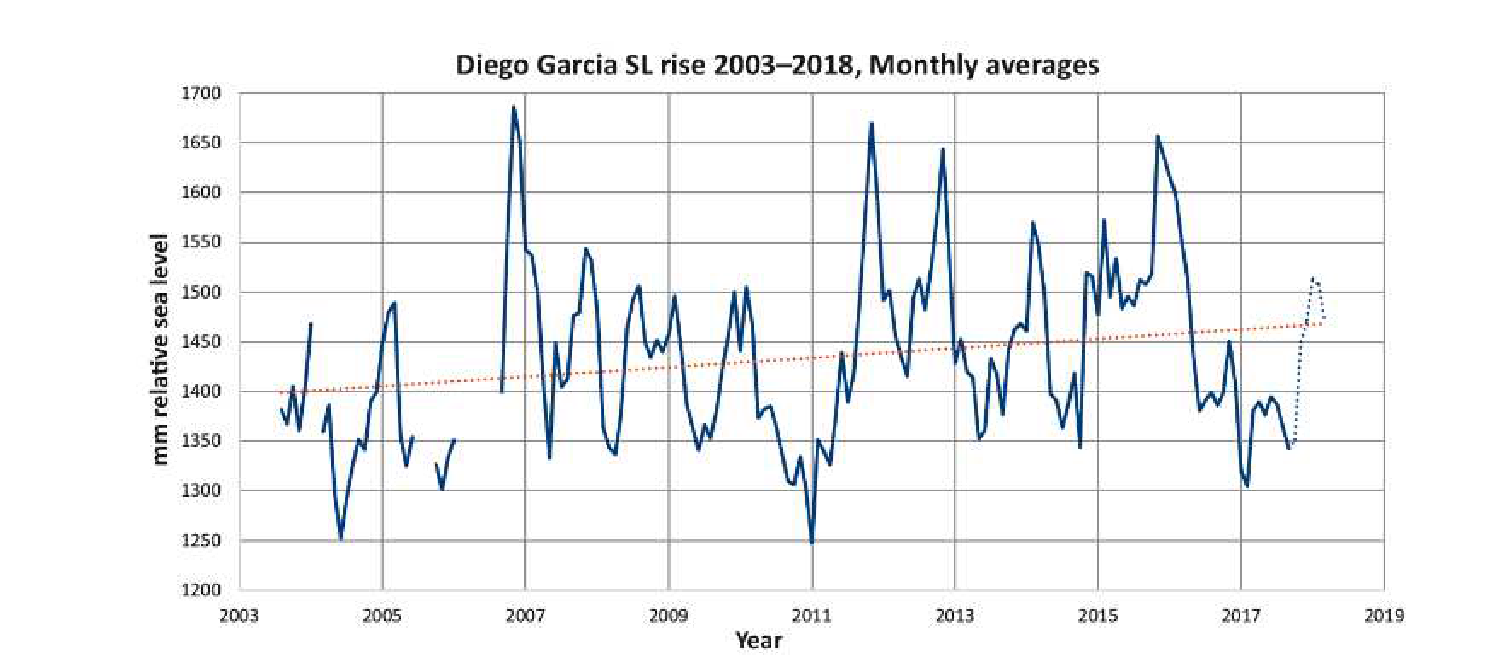

Rates of sea level rise in BIOT have tracked global averages for the region, with current rates of sea level rise reported to range between 3.3mm and >6mm per year (for example, see the recent tide gauge record for Diego Garcia in figure 3).

Figure 3: Recent sea level rise in Diego Garcia. A plot showing monthly means taken from the Diego Garcia tide gauge (Sheppard and Sheppard 2019).

A rise in annual average rainfall has been observed in Diego Garcia since 1950 from 2,500mm in 1950 to over 3,100mm at the end 2019.

From an initial long-list of impacts on biodiversity and society for this region, three priority climate change issues were identified by a regional working group of scientific experts and policymakers:

A key priority on BIOT is the restoration of natural nutrient cycles by eradicating invasive rats and restoring seabird populations. Seabirds are key components of tropical island ecosystems, transporting nutrients from the open ocean to islands, enhancing the productivity of island flora and fauna and that of surrounding marine ecosystems such as nearshore coral reefs.

Seabird-derived nutrients enhance calcification rates, including growth rates of corals, and enhance processes that produce island building sediments. New research shows that seabird-derived nutrients can return to both tropical islands and nearby coral reefs less than 20 years after rat eradication, although full recovery may take several decades. Seabird recovery can be significantly enhanced through rehabilitating native vegetation to over 50% of its original state, once predators have been eradicated.

As a fully protected MPA in a remote location, BIOT provides a globally important reference site for climate change impacts that can give insights into finer scale vulnerability and resilience in the absence of other anthropogenic stressors.

More detailed climate model projections of future coral bleaching conditions for BIOT and the broader Indian Ocean will soon be released. Whilst these will show the most vulnerable reef areas within BIOT, it already has full protection so has less direct management implications than this does for other locations within the region.

The restoration of island ecosystems through the eradication of invasive rats and restoration of native vegetation is the quickest and most effective way to restore seabird populations and the associated nutrient pathways that build resilience against climate change impacts. This is a priority conservation issue for BIOT.

As current global and regional projections of future climate change all suggest that severity and frequency of destructive ocean heatwaves will increase, there is clear urgency to limit future global warming and protect the ocean.

There are opportunities for more regional engagement to increase climate smart ocean protection that allows species range shifts along climate gradients, for example, exploring how MPAs in the region act synergistically.

Please cite this information as Koldeway, H., Atchison-Balmond, N., Graham, N., Jones, R., Perry, C., Sheppard, C., Spalding, M., Turner, J., and Williams, G. Eds Howes, E.L. and Buckley, P. (2021) Summary - key climate change effects on the coastal and marine environment around the Indian Ocean UK Overseas Territories. MCCIP Science Report Card 2021.

MCCIP wishes to acknowledge the contributions of the Indian Ocean Region Workshop participants who helped to identify the priority climate change issues: Samuel Bullen (BIOTA), Peter Carr (University of Exeter/ZSL), David Curnick (ZSL), Rob Dunbar (Stanford University), Helen Ford (Bangor University), Graeme Hays (Deakin University), Malcolm Nicoll (ZSL), Chris Perry (University of Exeter), Brett Taylor (Australian Institute of Marine Science).